Innisfree, 1970-1998

By Tom Rue

Chapter 4 - Welcome to the camp

During the month of June 1970, Bud Rue (my father) sat with me under an Innisfree pine by the front wall by River Road and informed me straight-out that from then on I was "free" to make all my own choices, including those the outcome of which could alter the rest of my life. We did not get too specific with "what if" speculation. He simply said he hoped I would take his and my mother's wishes into account when making decisions, but at just shy of age twelve, as my father told me, I was now free! At least in theory. At the end of the summer, I learned that I would soon be entering sixth grade.

But an argument over where I would live ensued, after which I ran out the door, down River Road toward the general store, and hid in the loft a friend's barn. My blatant rebellion was curbed eventually, but when autumn arrived, my struggle continued. I did NOT want to return to New Jersey. That conversation with my father, and my subsequent determination to "live at Innisfree" (which became a metaphor for freedom) impacted much of my adolescence and even later in life. In my childhood, and maybe for some other people, the connection to Innisfree was not just familial and social, but also in some sense mystic.

Any reader interested in a curious literary aside on the meaning of the Innisfree" poem, see Genevieve Pettijohn (2017), "The Magic of Yeats' "The Lake Isle of Innisfree": Kabbalism, Numerology, and Tarot Cards," in Criterion: A Journal of Literary Criticism: Vol. 10: Issue. 1, Article 10 (at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/criterion/vol10/iss1/10).

It should not be surprising for such a shift to be disorienting. And it was. In an eight-page autobiographical summary (written half a lifetime ago in 1978), my mother, Ann Rue, who now lives in Pike County with her wife Karen, recalled Innisfree briefly:

After a couple of years I finished my course work in the masters program [though she did so a decade later)]. I didn't complete the final requirements of a comprehensive exam and student teaching as our lives at that point [1970 onward] became consumed with Innisfree. I'll not go into the details of Innisfree's planning and creation, as that was really your father's thing and I merely shared a part of it. However when it actually came into being it consumed all our lives. It must have been very hard on you kids to have your parents move out of the family setting into the focal point of this teenage community. Your father ended up hospitalized from the emotional stress and lost his job. I felt when that happened as if our world was flying apart and I had to hold things together, with little less than my bare hands. You had become radicalized, defiant, and [were] doing crazy things not the least of which was bizarre acting out at school. Post Innisfree was difficult to say the least, but Innisfree to me was really worthwhile. I'd had a rather limited experience outside the home prior to that point, and in the midst of all the craziness that existed at Innisfree I felt a sense of being valued and respected by adults and kids alike. And this respect was not because I was somebody's wife or child or sister (the baggage I'd carried from my own childhood) but because I was me. And of course we still have the place and have enjoyed the setting since. It may sometime in the future become our home or the site for a new endeavor.

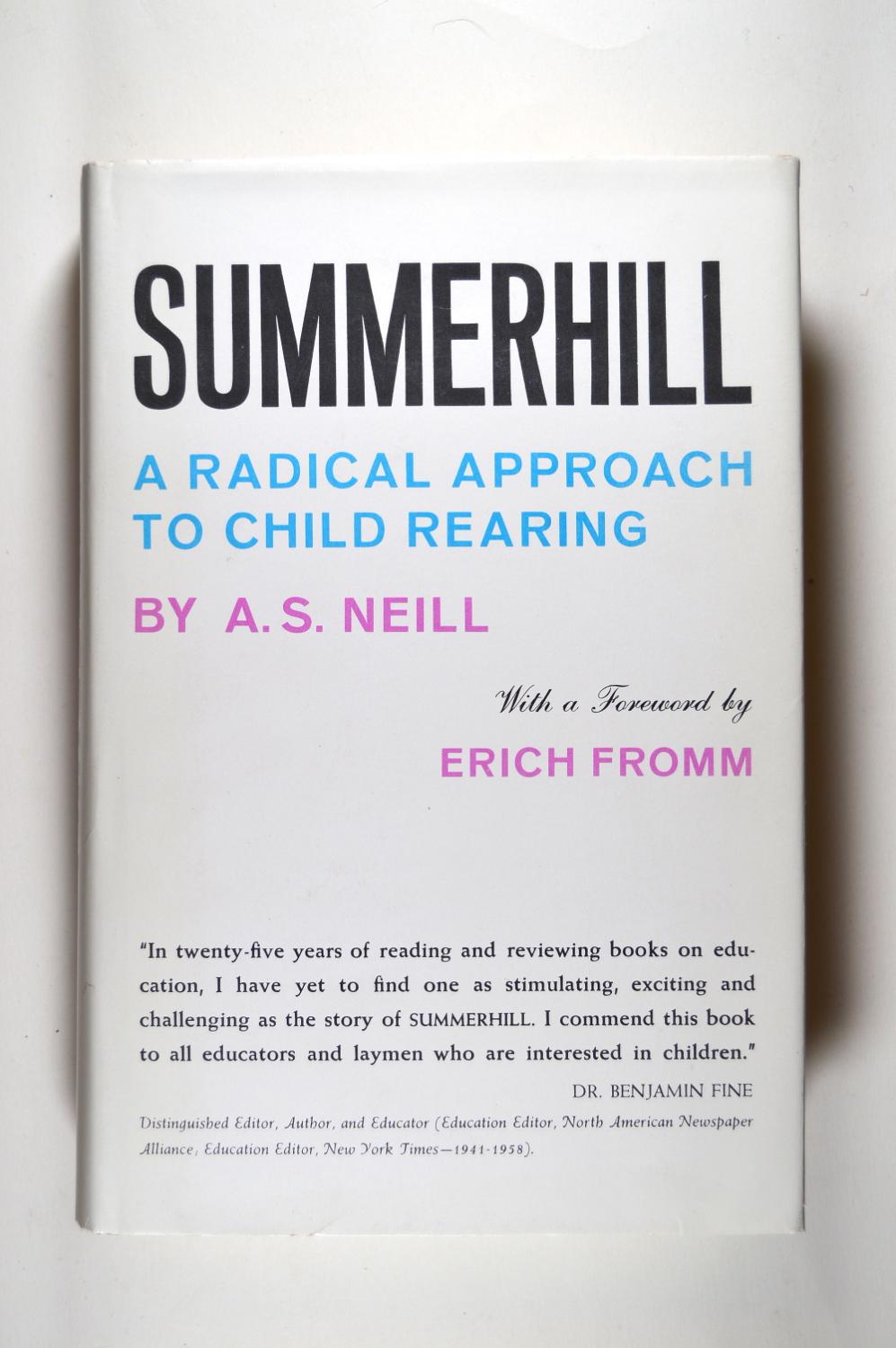

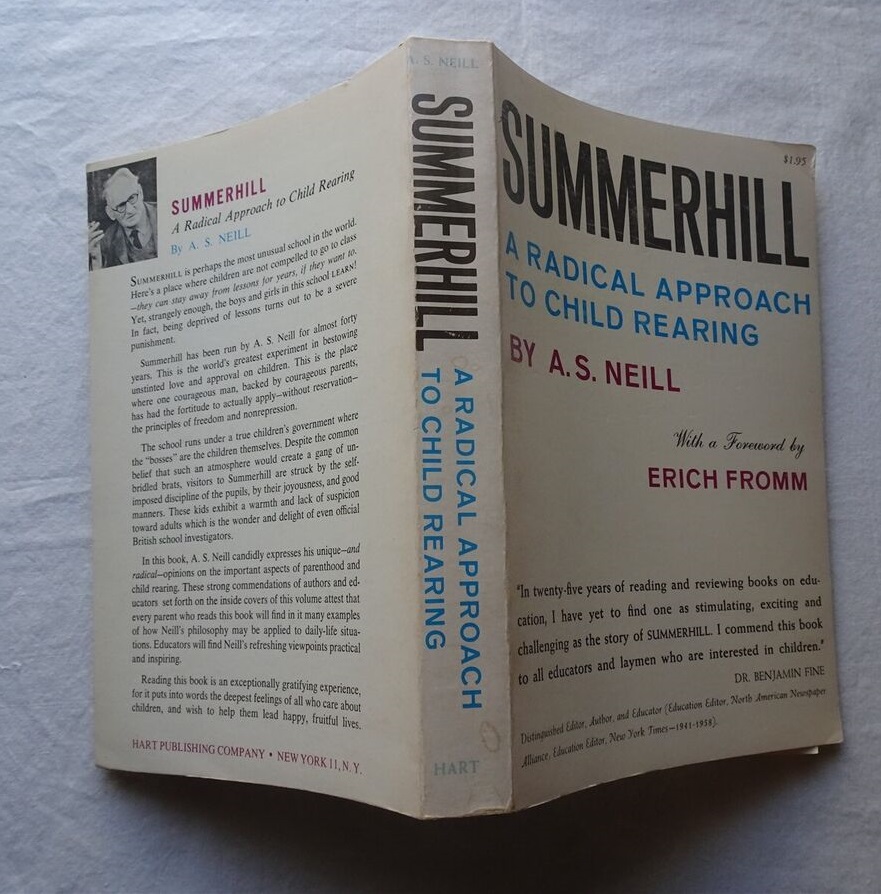

Ann Rue's retrospective assessment of the systemic impact that the formation of Innisfree had on the Rue family, and on myself, not to mention on her own personal development, was correct. Rapid swings between A.S. Neill's "radical approach to child-rearing" (the subtitle of Summerhill) from more traditional, then back to more conservative or centrist approaches to parenting and politics, swinging between right, left, and center, can be disorienting and unsettling for kids. As a young teenager, with my parents' active embrace of the Summerhill model for societal change, their recognition and denunciation of "oppressive" traditionally patriarchal rules and social order; and with my father declaring that I was henceforth "free", I read the whole book and latched my mind to the philosophy espoused by the Innisfree founders and campers and self-described revolutionaries who arrived at Innisfree initially as guests and stayed on.

Some time later I learned of a second volume by A.S. Neill -- Freedom Not License!, the title of which epitomizes Neill's Summerhillian philosophy. "Every child is entitled to freedom; an excess of freedom constitutes license. Freedom deals with the rights of the child [or of the adult]; license constitutes trespassing on the rights of others," according to jacket summary. Responsible exercise of freedom takes into account others' property rights and bodily autonomy. It requires honesty, respect, trust, and sustainability (in many senses). Consistent with this, human fulfillment, or self-actualization, involves the ability to reconcile and integrate opposing elements, such as freedom and limitations, because it reflects the complexity and balance of real life.

The early Innisfree community included many wonderful people, several of whom returned for reunions at multiple times held in Millanville and Skinners Falls. into the 1990s. A couple served on the Innisfree board of trustees. Some have remained in touch.

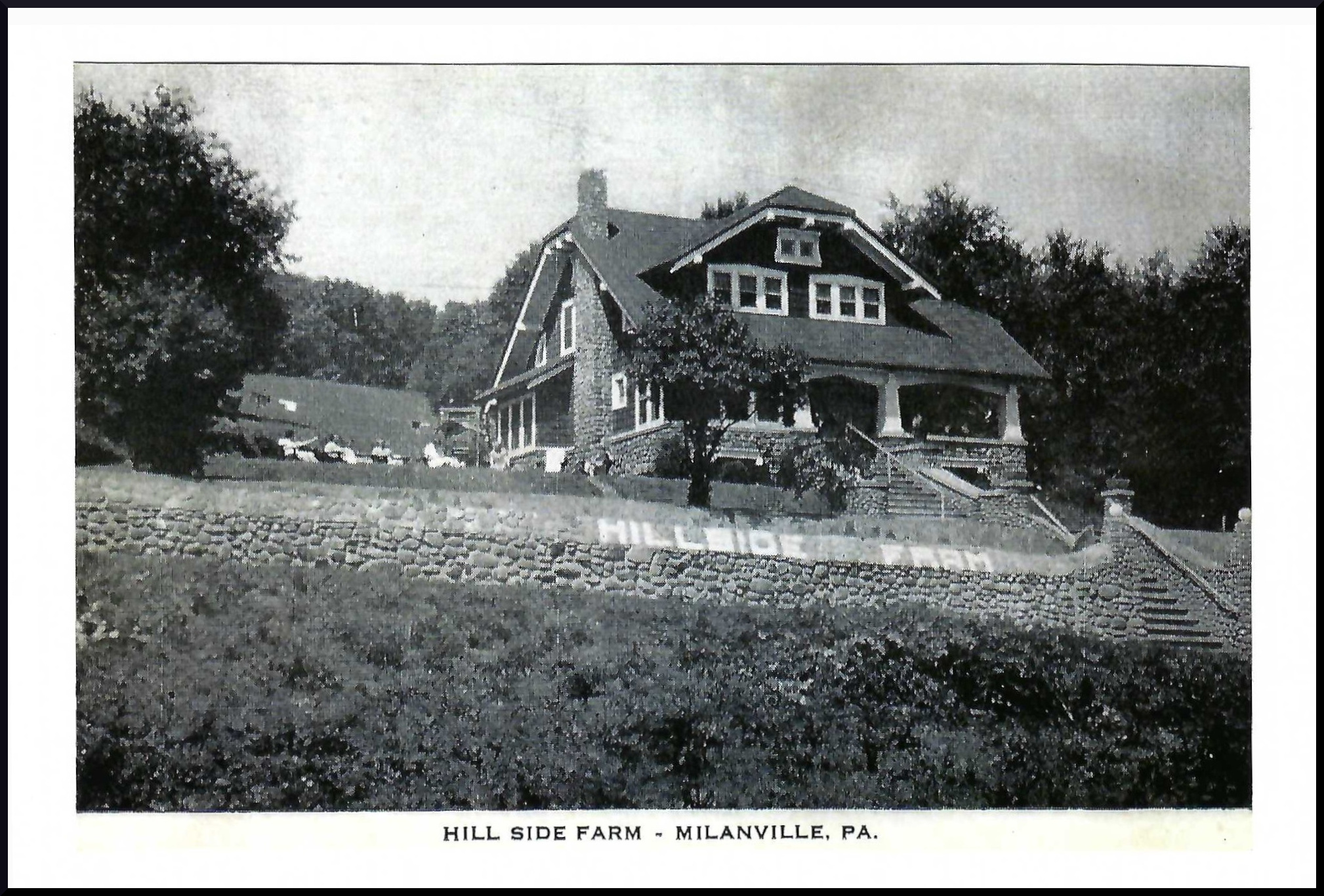

Early in the summer of 1970, kids from Innisfree began exploring Milanville on bicycle and on foot. During the camp's first summer of operation, an energetic group of young adults and teenagers traveling in a yellow school-bus in the direction of Madison, Wisconsin arrived in Milanville to visit friends when their bus broke down. They had it towed to a Damascus auto shop operated by local native Ben Lowe for diagnosis and repair. As the bus underwent repairs, a group of a dozen or so self-described revolutionaries wound up staying at Innisfree. Unfortunately, the mechanical prognosis for the old yellow bus getting back on the road was not good. For the next while, it could be seen in Ben Lowe's former junkyard. Innisfree campers first encountered these "bus people" while cycling around the area and invited them to the camp for a place to stay.

The bell was rung for a general meeting to be held in the rec hall. After a lengthy and more intense than usual debate, the consensus of those present in the rec hall big room was that the new arrivals were welcome to stay. Power to the people! The bus eventually turned to rust, but some of the travelers remained and shaped the direction of the remainder of Innisfree's first summer program, as well as ensuing years. Some of the "bus people" were from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx and, when they could, offered their apartments in the city as free places where we could stay as long as desired, returning the hospitality that they found at Innisfree. For a time, some rented an apartment over the Milanville General Store. This sense of Innisfree's early self-definition as a community and social experiment expanded to and from these remote locations. In later years, Innisfree's not-for-profit organizational mission in its later years became simply providing hospitality and a venue for a variety of educational, spiritual, and community programs and maintaining a place to do that.

The pastoral tenor of River Road was at times offset by the nightlife of what is no doubt widely remembered as a loud and wild biker bar called The Black Horse Inn. Living across the Milanville Bridge as a young teenager, from my present-day perspective, the establishment was out of control. I believe the owner and bartender was a man named Fritz, though there might have been others. At the time, I was just pleased to be served beer and be treated like an adult... as long as the place was crowded and the owner too busy or drunk to bother asking for ID. In 1975, Robert Lander, Sr. of Narrowsburg bought it under the corporate name of Ten Mile River Enterprises (see the attached county real property database card) and operated it for a time as the Lenape Tavern. According to his son Rick Lander, the company later sold the tavern due to the cost of liability insurance.

At ages eleven and twelve, I was served beer in the Black Horse bar and was allowed to sit and drink with friends and others with whom I had walked over the bridge. There were fights, not involving us. I recall one sexual assault that took place in the Black Horse parking lot during those years. The now long-gone saloon's reputation combined with that experience suggests to this writer there probably were others. The building, now the home of Gabriel and Floarea Vladu, still stands, according to a June 2, 2024 article in The River Reporter.

Another memory of the Black Horse during the summers of 1970 and 1971 was how the substantial crowd that filled sometimes filled the dining hall at adjoining tables. Some reacted with joy and celebration when a then current hit "Jeremiah Was a Bullfrog" came up on the jukebox. A sometimes louder audience response followed playings of "I'm Proud to Be an Okee From Muskogee". After a visit to the Black Horse, a dip in the river by the "peace rock" was a common occurrence, with or without bathing suits, with or without sunlight. Another favorite swimming spot was a waterfall that Innisfree bicyclists discovered in Fallsdale, then (and now) owned by the Tolson family. Miki Cowley, a close relative of the Tolsons, later served for a couple of years on Innisfree Corporation's board of trustees.

Folk music and rock-and-roll was an important element of the early summers at Innisfree. I recall a going with a group of Innisfree kids to watch the Woodstock movie at the Park Theater in Narrowsburg. The influence of the Aquarian Festival held the year before was evident at Innisfree. The early seventies was also a time when memories of the Stonewall riots in New York City and other unrest around the country were fresh. Consciousnesses were being raised to gender and sexual diversity, to moving past patriarchy, to feminsm, to peace, and to racial equality. Popular music of the time reflected these changes.

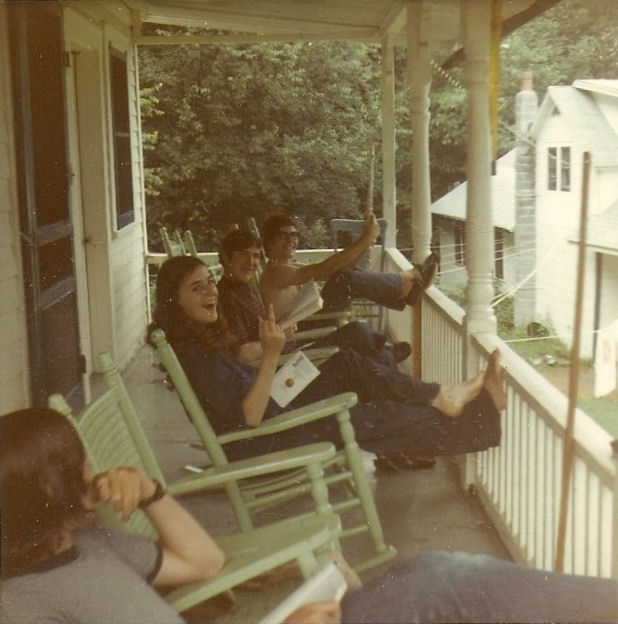

There was no formal instruction, but impromptu concerts by participants including Peter LeVine, Jordan Chassan, Joel Bluestein, John Peterson, and others, were common. Whether on the rec hall lawn or on the front porch of the main house or dorm or elsewhere, any one of these folk-singers would quickly gather a crowd and sometimes other guitarists. In later years, Peter went on to practice psychology in California, using music as one component for treatment of the effects of psychological trauma. Some others went on to distinguished professional careers in music and musical publishing.

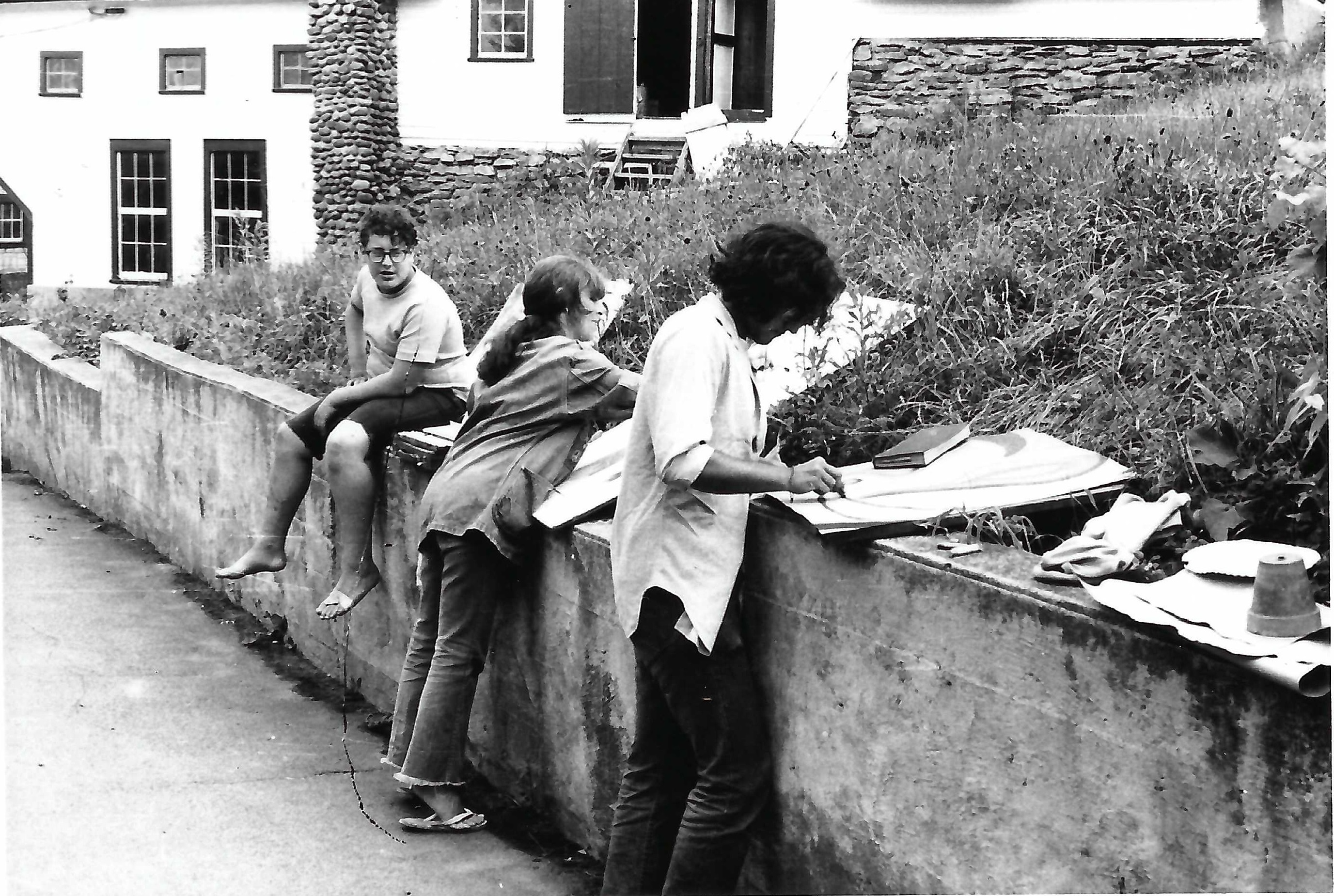

The theoretical model of the first summers of Innisfree in Milanville was Summerhill, though the name of that English school was rarely invoked that I can recall during Innisfree's meetings after the initial pre-incorporation phase in Montclair. We hoped to try our own hand at communal self-government, with A.S. Neill's anti-establishment ideas woven into Innisfree's philosophy. Commencing in June 1970, this took the form of a summer-long intentional community divided into two terms (some attended one, some both). At the outset, it was agreed the community had no rules and was essentially a blank slate except for the consciences and good will of participants. It was understood that future decisions governing the community would be by consensus. It was said that general meetings would last all night if consensus was not reached. Some did last all night. My recollection of general meetings is mixed. Some meetings were successful; others ended in frustration.

The actions of Innisfree kids sometimes leaked into the community and led to small conflicts. According to accounts that I heard from more than one source, one summer day in 1970, neighbor George Hocker walked up the drive and asked to speak to the camp director. Quickly, accounts agree, the conversation's tone escalated.

Mr. Hocker was understandably upset about a peace symbol that an unknown person had painted on the Township Route 63027 in front of the Innisfree property. As the two men spoke at each other, one defending free speech, civil disobedience, and alternative teaching approaches, etc.; and the other objecting to the "broken cross" as an evil and un-American symbol (made worse by the fact that someone had vandalized a township road with their call for peace), my mother approached to see the cause of the shouting. Suddenly, both sides quieted when she injected, "We'll cover it up!" (meaning with black paint or coal tar emulsion). This was soon done. Bud Rue was one of the people I heard tell this story, using it to illustrate the healthy and calming influence that his wife often had on his reasoning. There was no valid argument for tagging graffiti on the River Road and it was painted over.

The same summer, some unknown person painted a large white peace symbol on the large rock (historically sometimes called the "rafting rock") in the Delaware, presumably using some kind of enamel paint since the rough image remained for a few years. This led to the name "peace rock" which is still sometimes used in conversation. I truly have no clue who tagged either image. It is not unfair to guess that someone from Innisfree might have been responsible for both incidents of vandalism, but I have never heard anyone's name mentioned in connection with either action.

Another example of local residents taking issue at the manner in which Innisfree campers expressed themselves occurred as a result of the party line that Innisfree shared with an unknown neighbor. Granted, who would want to share a residential phone line with a "camp" with 60 young people and adults monopolizing the phone? However, a complaint was made to Big Eddy Phone Co. that Innisfree campers were using swear words during some of their phone conversations, and the party that shared the line occasionally picked up their receiver and got an unexpected ear-full when the phone was in use. Reportedly, one camper was removed from the program by her parents because an offended neighbor listened to enough of her conversation that she was able to identify the girl's parents in Montclair, New Jersey, and called and let them know what they overheard their daughter saying. After that occurred, Innisfree secured its own private phone number so as not to impose on inquisitive neighbors.

After the summer of freedom ended, I was enrolled in sixth grade at a conventional public school a few miles from Innisfree where the teaching approach did not at all resemble that which I was coming from. I became also educated even more than I had been during earlier grades on what my father called the "oppressive" nature of compulsory public education. Even beyond what I expected based on my prior experience as a public-school student in my earlier school years in New Jersey, I was unaccustomed to the lawful application of corporal punishment of students by teachers. At that time, the practice as I experienced it at Damascus School was one of being smacked with a ruler more than once for the offense of talking back. It did not teach respect; just surprise and annoyance which could have escalated though it never did. I also recall school science lessons taught in a manner that seemed heavily influenced by the religious beliefs of the one teaching, more so in science than in other subjects. It was quite a dramatic snap back to authoritarianism from the reality that I had experienced at Innisfree. My view of the learning experience provided by the public schools I was forced to attend (until graduating a year early to get away from home) was shaped in part by the writings of A.S. Neill. Fortunately, or unfortunately, during the rest of my public-school education, though at least one application was made on my behalf while I was in eighth grade, I completed the requirements to graduate high school amid what my father and his colleagues had formerly described as an "oppressive" system, but in which he had continued to participate by teaching in traditional public schools for as long as he did. This philosophical evolution was something he discussed later in his life, which I understood.

From my childhood through completion of graduate school, much of my family's and my own energies were devoted to Innisfree in one manner another, whether it was the never-ending physical maintenance of the property (which my parents paid local people to do or did themselves), legal correspondence with state licensing agencies and AYH, promotion and marketing, and countless other tasks (much of which I did as the nonprofit corporation's secretary). In 1976, I went away to college in Utah, thereafter living in two other states out west until returning east in 1981. When I returned home, my parents had just days before been served with a summons and complaint in a civil lawsuit by a former friend, which will be described in more detail hereafter.

During the early seventies and eighties, Innisfree was licensed by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources (DER) as a organized summer camp and as a public eating and drinking place but was not your typical children's camp. Throughout his high school years, Innisfree founder Bud Rue himself worked steadily as a camp counsellor at a Clearlake Camp near Battle Creek, Michigan, attaining the rank Eagle. Whether or not any of the experience he gained in a youth leadership role at a summer camp affiliated at that time with Fort Street Presbyterian Church in Detroit aided his vison and contributions to the Innisfree project is unknown, but they probably did to an extent, though the programs themselves were vastly dissimilar.

The idealistic vision that seemed to move Innisfree's first organizers was the formation of an intentional community in which all members participated in community self-government by consensus, offering freedom and accountability, leading to the responsible exercise of freedom that is at once mindful that the consequences of one each person's impacts on others and on the planet. The program was modeled after Summerhill by A.S. Neill, which has been called "the first Libertarian school". Innisfree's founders, which included high school students, teachers and other professionals and in some cases their family members, later joined by others who landed at the place over the summer, some staying as long-term guests, emphasized a program including sensitivity training (T-groups) for personal growth, general meetings for community decisions, and maintaining the property by group effort.

The June 2, 1970 issue of The Wayne Independent reported: "The staff, under the direction of Bud Rue, Montclair, includes two mathematic teachers, an English and drama coach, musicians, school psychologist, a noted New Jersey artist, journalist, nurse and other professionals. The camp, named Innisfree after W.B. Yeates' poem 'The Lake Isle of Innisfree,' was founded with the intent of offering teenagers the opportunity to experience self-direction."

Most active among the promoters were three couples -- the Rues, the Browns, and the Maylones, though well over a hundred of all ages were involved in the original organization -- which was initially dubbed "the Summerhill Association," with the intent of modeling a school in Milanville after the alternative educational institution founded by A.S. Neill. The program concept was modeled after the famous free-school in England described by A.S. Neill in his book Summerhill, though the Innisfree program had to be conceptually downsized to a camp, due to difficulties becoming chartered as a school by the Pennsylvania Department of Education. To aid with fund-raising and promotion, a publisher donated a case of copies of Neill's book for distribution with materials about the proposed camp.

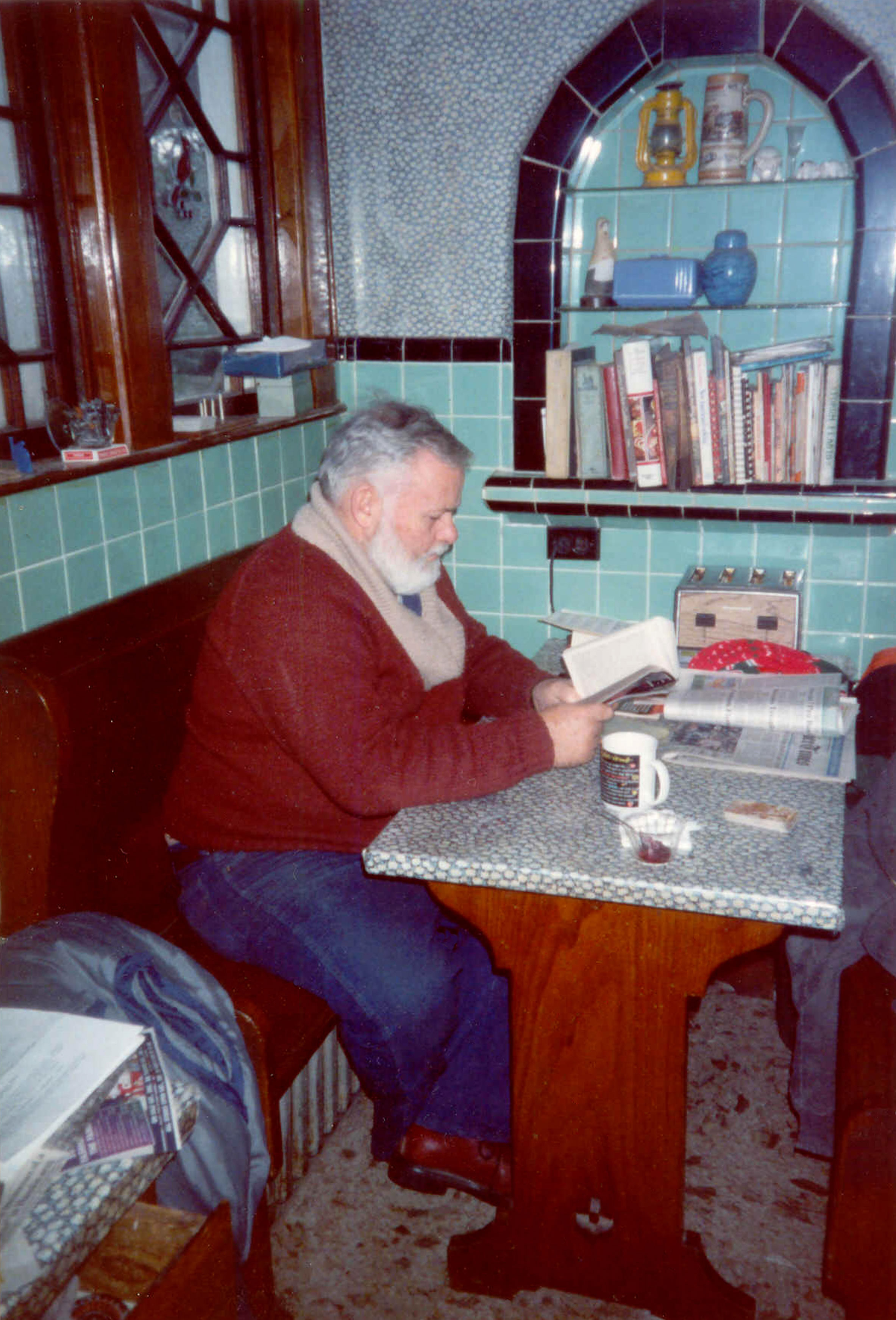

Bud was recognized by Innisfree's early participants as the project's initiator and a chief source of its energy. It took Bud's zeal (perhaps exceeded only by the mania of A.J. Thomas) to bring to fruition a plan developed by what a brochure written by Ann Rue called "this starry-eyed group of idealists."

Funding sources for a down-payment on the Milanville property were channeled through the Sanfurd Bluestein Foundation of Montclair, itself a major contributor to the project. Professional fund-raiser Peter Malcolm of Montclair made a sizable contribution which, at the time, he chose to do anonymously. Benefitting from the tax-exempt status of Innisfree Corporation, over ensuing years donations of money, corporate stock, furniture, equipment, used clothing, books, and other materials, by individuals and corporations for Innisfree and its participants continued to flow. The large number of books that were brought to the camp by various visitors, guests, and participants developed into a free library that was offered for anyone's use. At first, the books were shelved in the rec hall big room, where dances were held. Later, we relocated it to the front two rooms on the first floor of the dorm.

In 1970 alone, minutes of Innisfree Corporation and other records show the following individuals made donations which helped make the purchase of the camp possible: Ford Schumann of Montclair, Sanfurd Bluestein of Montclair, Roy Sackett of Glen Ridge, Clyde Rue of Montclair, William Brown Jr. of Montclair, Peter Malcolm of Montclair, William Woldin of Bound Brook, Charles Gehrie of Montclair, William Brown Sr. of Lantana, Florida, Mr. and Mrs. Lee Condelmo of Piscataway, Vickie Kaufman of Montclair, Doris Lada of Montclair, Ted Tiffany of Paterson, and Charity Eva Runden of Montclair. One other donor was John D. Rhodes, who visited the camp with a friend in 1972 and, on July 25, made a gift to the corporation of 170 shares of Rank Organisation Ltd., Inc. valued at $4,696.25. Undoubtedly, this list is incomplete. If you know of others, please let me know.

Innisfree's founders also included dozens of high school and middle school aged students from Montclair, in addition to the adult staff. The incorporating trustees that got the ball rolling with the first summer's program included the following: Bud Rue, (president), P. Clarke Maylone (vice-president), Gail Wilson Brown (treasurer), Ann Rue (secretary), William W. Brown III, Peter Malcolm, and Sanfurd G. Bluestein, M.D. Most of these people were Montclair teachers. Dr. Bluestein was a radiologist whose son was an Innisfree participant, and Mr. Malcolm, as noted above, was a professional promoter. Without their energy and real-world contributions, Innisfree would never have come about.

The camp philosophy was based on ideals of self-government, group decision-making, and individual responsibility. It was the summer after the so-called "summer of love". Participants in the Innisfree "camp" program came for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was to take part in building a community in which members could learn about themselves in relation to others.

When someone at Innisfree rang the dinner bell, other than at mealtimes, all 60 community members were expected to assemble and participate in a group process until the problem (whatever it was) was resolved by group consensus.

One meeting, outstanding in the memory of this writer, had to do with theft at Innisfree. After a few hours of discussion, it became clear to all that the root of the problem was that some had, while others had not (or at least not as much as they wanted). A simple solution was agreed upon. Consensus was that a "pot" -- actually, it was more like a Tupperware bowl -- would be placed in the living room. Anyone who had money to spare would place it in the pot. Those who needed it would be free to take as their needs required. Pure socialism, in a teapot. As the vessel made its way around the room, generous idealists filled it with paper currency and change. Finally, it was placed on the shelf.

There would be no more stealing. The money belonged to everyone, so stealing was not possible, the group concluded. "From each according to his ability; to each according to his need," someone quoted hopefully.

The next day, the meeting bell rang once again. The money pot was empty! A quick investigation revealed that the six-year-old son of Innisfree's founder, who himself had been a central focus of the original discussion had helped himself to the entire amount and purchased a stock of candy at a local store. After all, he asserted, it was his right. The child (who grew up to be a successful lawyer) simply took what was up for grabs.

Adding insult to the community's injury, the young entrepreneur opened a "store" of his own on the Innisfree lawn, arranging chocolate bars on the top of a small crate with a board affixed, and doubling their sale price. Penny candy went for two cents, a nickel chocolate bar for a dime, etc. Not surprisingly, some campers bought from the "store" on the lawn; to save themselves the one mile walk to the Milanville General Store.

Many years later, in a public Facebook group called Innisfree 1970-1971, a few early participants shared their memories of those years, of which these are a representative selection of those who replied:

- Jo Qatana Adell: "Kym Wicks was supposed to be there for the whole summer but got Sent Home due to an eavesdropping phone operator in Milanville calling her parents & telling them what she was talking about in a private conversation."

- Nancy Creighton: "I was there for a short visit- must have been in 1971... as I recall, I had a problem with a horse (was thrown, dragged and stepped on). Otherwise, I loved my time there!"

- Akasha Holmes [Marcie Holmes]: "That first summer at Innisfree was fantastic for me. I was still very new in this country and saw it as an opportunity to get to experience Americans without my family. After all, I was at the beginning of my journey of becoming an American."

- Alexandra Roth: "Unlike everyone else, I did not have a great time at Innisfree. I wasn't prepared for the lack of structure and didn't have the self-esteem necessary to manage the interpersonal challenges. I remember a lot of it very clearly. It was formative, but not in a good way."

- Christine Hall: "Everybody got something different. I was there but not sure I actually registered. I participated in a lot. Slept a lot. I remember Bud telling me he thought I wasn't expressing my feelings honestly because I didn't have any complaints ... about anything or anyone. I hate it when someone tells me what I think."

- Tom Rue: "Christine Hall, I remember this message being endorsed and explicitly said in a T-group construct, more during the summer of 1970 than in later years when programs at Innisfree took many forms. I do not specifically remember my father (Bud) speaking those words, but it was part of the ethos that summer, and he probably did. I think it's safe to say the statement you recall was consistent with an Innisfree “statement of philosophy” upon which the first summer of Innisfree was modeled. Glad to hear you got plenty of rest there!" She then clarified: "I loved it. 😍 A memorable summer!!! "

Back: Chapter 3 - The Summerhill Association | Next: Chapter 5 - Separations in space and time